EnemyGraph Facebook Application

PRESS Updates:

NPR Marketplace

The Chronicle of Higher Education

MSNBC

Los Angeles Times

Mashable

Slashdot

Daily Mail UK

San Francisco Chronicle

Vice

TNT

BuzzFeed

and hundreds more just do a search on google news.

For the past six months my research group has been looking into an app that explores social dissonance on Facebook. Today we are announcing the public release of EnemyGraph. The project was developed principally by graduate student Bradley Griffith with invaluable help from undergraduate Harrison Massey.

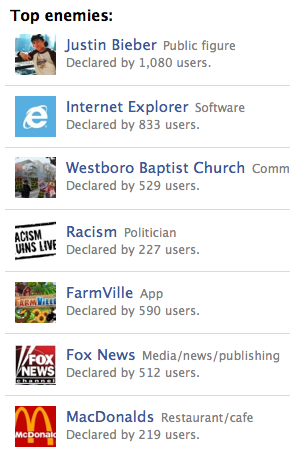

EnemyGraph is an application that allows you to list your “enemies”. Any Facebook friend or user of the app can be an enemy. More importantly, you can also make any page or group on Facebook an “enemy”. This covers almost everything including people, places and things. During our testing testing triangles and q-tips were trending, along with politicians, music groups, and math.

Most social networks attempt to connect people based on affinities: you like a certain band or film or sports team, I like them, therefore we should be friends. But people are also connected and motivated by things they dislike. Alliances are created, conversations are generated, friendships are stressed, stretched, and/or enhanced.

Facebook runs queries to find affinities. EnemyGraph runs what we call dissonance queries. So if you have said you like, say, Portlandia on your profile page, and in our app one of your friends has declared them an “enemy” we will post this “dissonance report” in the app. In other words we point out a difference you have with a friend and offer it up for conversation, as opposed to a similarity. Relationships always include differences, and often these differences are a critical part of the fabric of a friendship. In the country club atmosphere of Facebook and it’s platform such differences are ignored. It’s not part of their “social philosophy”.

EnemyGraph is a critique the social philosophy of Facebook. On it’s developer splash page Facebook invites us to “Hack the Graph” - and so we did. We give them a couple of weeks at best before they shut us down for broadening the conversation and for “utilizing community, building conversation, and curating identity” their three elements of social design. EnemyGraph is a kind of social media blasphemy.

The ironic thing is - and this is a byproduct of the project rather than the intention - we are generating a whole new set of personal data that could potentially be mined. I found it a compelling tool for self expression, at least as powerful as the likes list on your Facebook profile page. Often, it tells you a great deal about a person in a way that an affirmative list can not. The first thing my colleague Dave Parry though of to list, for example, was venison, which says a lot by itself.

I’m sure there are new algorithms that can be developed around what you can sell some one when they don’t like X or Y, and conversely what they will like, what kind of person they are, etc. Or, similar to an idea Clive Thompson mentioned to me, find out what I might like or dislike based on a set of dislikes I share with others. We’ve thought about it and think there’s actually a positive social value in all this. Alliances between people around social and political issues are one thing. There are also interesting ways to connect to people that you never would have known by affinities alone. The group that has made venison an enemy might have never encountered one another. And of course there are also likely ways to structure business around it (which is why Andrew Famiglietti thinks maybe Facebook will leave EnemyGraph up, even while they hold their nose). But our interest for this project is a simple, expressive, often fun critique of the lopsided Facebook approach to online mediated social interaction.

A few people have asked us about the potential for misuse. Beyond the obvious fact that every tool can be misused ours is all opt in. Also, based on our test group, it’s also mostly in jest. (I’ve been to top enemy among my friends all through testing). If you are not friends with someone, or not a user of the app, or generally not famous, you cannot be listed as an “enemy”. We will also monitor the app closely for abuse.

Because of the fact that you can make pretty much any object, place, or thing that has a FB page an “enemy” EnemyGraph is in some ways an unfortunate name. So it’s not just a list of people. In fact you can have an entire list with no people on it at all. In a way we are misusing the word “enemy” just as much as Facebook and others have misused “friend”.

One early user described EnemyGraph as a way to “interact with your friends over common enemies … creating alliances based on shared animosities”.

How the project was made:

When I saw the first friends list at the beginning of the social media era the first thing I thought was “where’s the enemies list?” No one ever made one, so we did. We actually started out working on something called UnFriends. It was in the aftermath of undetweetable, which generated plenty of attention, but was shut down by Twitter in 5 days. After coming across some language from Facebook saying an app cannot encourage unfriending we decided to shelve what was nearing a finished application. We knew it would last only a day or so. So we moved on to what at first we called EnemyList, which was just that simple. Once we figured out you could add any FB page it became EnemyGraph - playing off “social graph”. The project was developed almost entirely by Bradley Griffith over the course of a few months, with invaluable research help from Harrison Massey. Bradley is an Emerging Media + Communication (EMAC) graduate student and Harrison is an undergraduate.

As to how it fits in with the research agenda of my lab, we look at EnemyGraph as a test to learn from for the new project we are about to start on for this semester. Because these kinds of tools have not been available previously we are interested to see how they are used. We plan to take what we learn and apply it to an outside of Facebook site that explores similar territory, but in a broader fashion.

_